Owning companies linked to forest destruction risks major financial losses. But focusing on engagement and demanding transparency and supply chain discipline could bring rich rewards.

Deforestation linked to growing commodities demand presents significant risk of loss for investors, but also opportunities to benefit by engaging companies and adding to pressure for stricter policy actions.

Deforestation relates to unmanaged, unsustainable or illegal logging in areas of high conservation value. Harmful consequences include climate change, land grabs, community displacement and food insecurity.

Net forest loss disproportionately affects rural populations in low-income countries. By contrast, well-managed renewable forests can be sustainable and bring vital social, environmental and economic benefits.

Recent fires in the Amazon highlight the precarious state of the Earth’s rainforests. Over the past 50 years, 17% of the Amazon rainforest has been destroyed1. This has been linked to growing global demand for just four commodities: palm oil, cattle, soy and paper/timber products.

The big four

The majority of deforestation is driven by demand for palm oil, cattle, soy and paper/wood products. Other contributors are coffee, cocoa, sugar and processes such as mining and shifting cultivation.

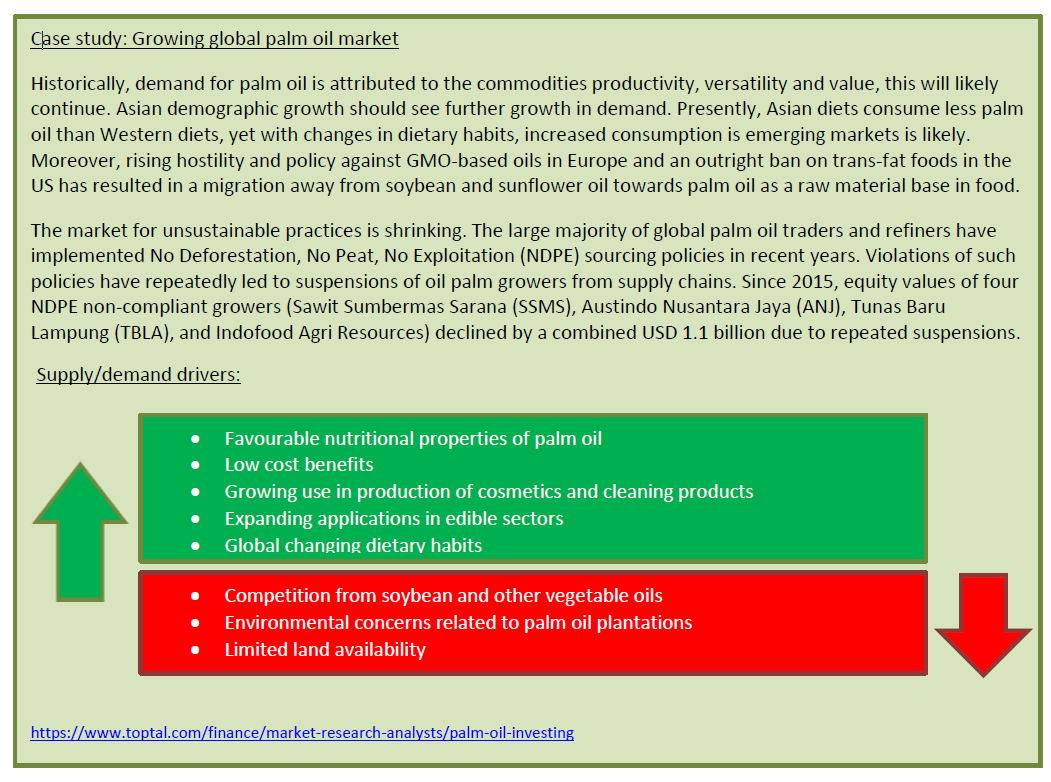

Indonesia and Malaysia account for 85% of palm oil production. The ubiquitous oil is contained in everyday products from chocolate and oven chips to cosmetics.

Palm oil production accounted for 2.3% of global deforestation between 1990 and 2008; 12,000 premature human deaths in 2015 caused by air pollution across Indonesia; the loss of critically endangered orangutans; and exploitation of workers and child labour. It underscores serious supply-chain issues.

However, the commonly held view that palm oil is unsustainable is a misconception. In fact, palm oil is critical for global food security; replacing it with other oils would only necessitate more deforestation.

Palm oil yields more per hectare than any other edible oil crop2. It makes up 35% of all vegetable oils, grown on just 10% of the land allocated to oil crops3. Moreover, it is the cheapest source of vegetable oil and an important food product for low-income groups worldwide.

Palm oil also has health benefits relative to other oils. It is naturally trans-fat free, while fortified palm oil is used by governments in Sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia to combat Vitamin A deficiencies.

Boycotting palm oil to combat deforestation is not a solution. Alternatives would require more land and could have negative health consequences. Instead, action should focus on making production less harmful.

Cattle farming

The conversion of forest to cattle pasture creates 80% of new deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon, driven by demand for beef and leather products. Beef production – which accounted for 7% of Brazil’s GDP in 2016 – is set to rise to meet global demand.

Media and regulators have focused on the Amazon biome, which has meant policies and initiatives across South America have become fragmented and unequal. Disjointed regulations merely displace the problem elsewhere. New frontiers are emerging across Latin America, and land clearance continues.

Additionally, growth in demand from developing countries across Asia and Africa puts pressure on beef production in South America. These markets have lower regulatory expectations, meaning unsustainable deforestation practices continue4. Investors must be mindful of exposure to these new supply chains.

Paper and wood

Demand for paper-based packaging is expected to rise as an alternative to plastic packaging. A challenge for companies will be to ensure that virgin fibres used in products originate from sustainably managed sources.

Most paper comes from “production forests” – fast wood-growing operations with harvesting cycles of 5-10 years. These can have a positive environmental impact, as seedlings and growing trees capture carbon more effectively than the agricultural land these operations may have replaced.

However, in Indonesia the drive for wood pulp has resulted in deforestation to create new ‘fast wood’ monoculture plantations such as acacia5. Investors should encourage companies to increase use of recycled paper and waste wood to meet increasing demand.

Separately, it is estimated that up to 30% of timber trading globally is illicit, while logging represents 50-90% of forestry activities in key producer tropical forests such as the Amazon Basin, Central Africa and Southeast Asia6.

Illegal timber is often laundered into the legitimate global timber trade. Traceability certifications – such as the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) or the Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification (PEFC) – are necessary to prevent this.

But these certifications tend to be applied in bulk weight, making it easy to mask the origin of a piece of timber. While certifications are beneficial, it’s time for governments to tighten regulations and demand better supply-chain disclosure.

Soy

Soybean production was responsible for 5.5% of global deforestation between 1990 and 2008, double the amount attributed to palm oil. World soybean production has more than doubled in the past 20 years due to demand for soybean meal as animal feed, biofuels and products such as meat substitutes.

The fastest growing soy importer is China, where rapid meat consumption points to a steep increase of soy imports for animal feed7. New tropical regions are also being exploited increasingly as advances in farming methods and crop varieties make it possible to grow soy in tropical soils.

Evidently regulation has a part of play. Brazil has enforced a new Forest Code; the EU has extended action on deforestation to soy; and international climate efforts are leading to stricter policies on local land-use.

Initiatives such as the Brazilian Soy Moratorium in 2006 have reduced deforestation in the Amazon biome. But this increased deforestation in other South America biomes, where land costs are lower and environmental protections fewer.

It highlights how divesting from problematic areas may have unintended consequences. Engaging with ‘legal’ deforestation or avoiding sourcing from an area does not mean the problem is solved.

Investment risks

The climate impact of mass deforestation is likely to translate into market-wide losses. The effect of deforestation on rainfall patterns is reducing agricultural yields. This will impact profits directly.

Since 2002, there has been a significant drop in productivity from soy, maize and coffee industries, largely attributed to changes in rainfall patterns due to forest degradation8.

Further, if market conditions change or regulations limit production from newly deforested land, forestry or agriculture assets could experience write-downs, devaluations or conversion to liability.

The physical impact of climate change could also render newly deforested land unusable. More than six million hectares in Indonesia – 28% of the nation’s land bank – are stranded after the government halted new palm oil licences and imposed a moratorium on permits for forest and peatland. Investors should ask companies if they have quantified the proportion of land at risk of becoming stranded.

Indirect financial losses can also occur. When Malaysian palm oil company IOI Group was suspended from the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) for violating its policy on clearing forests in March 2016, its share price fell 18%.

Other indirect risks include loss in creditworthiness. Deterioration in profit may mean a company fails to service debt obligations on time. There is also a risk that a company’s cost of capital will increase.

Then there is the risk of legal actions, sanctions and fines. Environmental breaches, and lack of preparedness to comply with regulatory changes, can adversely impact a company’s financial position. In addition, exposure of involvement with illegal activities could cause reputational damage across the supply chain.

There is also a risk that commodities associated with deforestation will see a fall in consumer demand. In 2014, EU labelling laws were changed so products had to state whether they contained palm oil.

Supermarket chain Iceland pledged to remove palm oil from all its products by 2018, but was called out in January 2019 for selling at least 28 own-brand products containing palm oil. Investors need to be cognisant of an investee firm’s pledges and transparency in supply chains to avoid customer distrust and loss of market share.

Investment opportunities

The drivers for increasing soy yields are three-fold: as a meat alternative; for animal feed; and as an oil for other consumer goods. The global market for palm oil is also projected to rise, driven by its ubiquitous applications, while paper-based packaging is experiencing a resurgence as an alternative to plastic.

It presents opportunities for investors to direct capital towards sustainable practices by demanding transparency and holding companies responsible to meeting targets.

More than 470 companies have committed to removing deforestation from their supply chains by 20209. Through engagement, investors can encourage investee companies to improve supply-chain transparency, set targets and establish a forest policy. Examples of disclosure best practice can be found on Forest 500, the world’s first forest ratings agency.

Separately, ethical consumers will likely pay a premium for sustainably produced items. Financial products linked to deforestation-free commodities or sustainability also offer opportunities, such as sustainable landscape bonds, green bonds and sustainability performance-linked loans.

In addition, sustainable intensification of land should be a goal. This process aims to increase yield per unit of land without adverse environmental impact or cultivation of more land. This may bring investment opportunities in areas such as biotechnology, precision farming, agroecology (e.g. intercropping) and organic farming.

Vertical farming similarly aims to reduce land-use whilst increasing food production, typically in an indoor environment. While critics argue that indoor farms are extremely energy-intensive and that the produce is too expensive to solve food security issues, there are innovators such as SkyGreens. One urban farm in Singapore produced 500kg of product in one harvest10.

Conclusion

The risks from deforestation are significant. Exposure of illegal practices in the supply chain and shifts in consumer demand are likely to hit companies’ reputations. There are numerous potential financial risks.

Ultimately, companies dealing effectively with deforestation and sustainability issues will perform better than those that don’t.

At the same time, investors are uniquely positioned to advocate a harmonised policy response and engage companies to increase transparency and set time-bound targets. Ultimately, firms dealing effectively with deforestation and sustainability issues will perform better than those that aren’t.

Deforestation practices are often illegal, deep in the supply chain and continue despite a company claiming to produce certified products. It underlines the need for in-depth supply chain analysis and improvements in product traceability.

1 The Economist – Deathwatch for the Amazon, 1st August 2019

2 WWW – 8 things to know about palm oil, 12th November 2018

3 IUCN Issues Brief – Palm Oil and Biodiversity, 2018

4 Innovation Forum – Tropical Deforestation: where’s the beef? 15th November 2018

5 Union of Concerned Scientists – Wood Products

6 Medium.com – Are we stopping illegal logging and timber trade? 14th June 2019

7 WWF – The story of Soy, 14th December 2016

8 Brink News – Why investors are backing zero deforestation, 11 October 2018

9 Prince of Wales’ International Sustainability Unit – Zero deforestation Commodity Supply Chains by 2020: Are We On Track? January 2018

10 The Straits Times – Vertical farm receives the world’s first urban farm certification for organic vegetables, 11th June 2019