This article was originally published on 3 October 2019 on Thinking Aloud.

Introduction

Our climate is changing. In recent years, we have seen an increase in costly extreme weather events such as storms, wildfires and floods. At the same time, we are living through the hottest years on record.

In 2018, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) published its Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5°C1 . This paper highlighted the environmental, social and economic damage we can expect if we don’t take more ambitious action to reach the goals of the Paris agreement2 — keeping global warming within 2°C, and ideally within 1.5°C, from pre-industrial times.

Limiting the consequences of global warming is one of the most significant challenges of our times. A growing population means rising demand for energy and food production. This releases greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, a major cause of rising temperatures. GHG emissions hit a record high in 2018. As they continue to increase in many regions, the scale of the challenge is immense, the urgency of action unprecedented.

‘We are the first generation to fully understand climate change and the last generation to be able to do something about it.’Petteri Taalas, secretary-general, World Meteorological Organization (WMO), 2018

A warming planet and the transition to a low-carbon economy are affecting the risk profile for many of the companies and economies we invest in. With changes in climate policies, public perception and technological advances, businesses need to be open to change and become more resilient. Assessing the risks and opportunities of climate change forms a core component of our investment research and approach to environmental, social and governance (ESG) integration.

As a fund manager, we have a responsibility to all our clients to consider how climate change will impact the value of their investments. We also have a critical role to play in providing finance for the transition to a low-carbon economy, and for the adaptation to the effects of climate change, through our products and investment decisions.

‘Investing in a Changing Climate’ is the first in a series of papers – Five Pillars of ESG Analysis – planned for this year and next. This series looks at the major themes within the ESG universe: climate change; labour practices; human rights; environmental responsibility; and business ethics.

This paper is also one of three on climate change that Aberdeen Standard Investments will publish in the coming months. Our Research Institute is producing ‘Going Green’, a comprehensive study that will demonstrate how different climate policies affect global greenhouse gas emissions. Going Green will showcase Aberdeen Standard Investments’ proprietary climate change modelling tool.

Looking at climate change from a different perspective, ‘Strategic Asset Allocation: ESG's new frontier’ will argue that ESG factors are among the most important drivers of long-term investment returns. This report, which includes a special focus on climate change, advocates integrating ESG analysis at an asset class level to supplement ESG analysis of individual securities.

Video - Climate change: investor risks and opportunities

It’s essential that investors understand the financial impact of climate change on portfolios. But as well as risks, climate change offers huge opportunities. ESG investment analyst Eva Cairns outlines our approach for identifying the winners – in particular, our emphasis on company engagement.

Video - Climate change: investing for a sustainable tomorrow

At ASI, we embed environmental, social and governance analysis into our investment process for all asset classes. This helps us understand the financial impacts of climate change on companies in which we’re looking to invest. In this way, we can allocate capital to those businesses that can help our planet and society, while also identifying good investment opportunities for clients.

Download this article

as a pdf

Understanding the

Changing Climate

Chapter 1

1. Our climate is changing

Our climate is changing in two key ways: gradual changes such as temperature and sea level rises, as well as acute changes due to more extreme weather events.

’Natural disasters in 2017 caused overall losses of US$340bn. This was the second-highest annual loss ever and almost double the previous year’s level – a figure roughly equivalent to the annual GDP of Denmark, Egypt or Israel. Insurers had to pay out a record US$138bn in losses.’ MunichRe

Temperatures are breaking records.

The 20 warmest years on record have occurred in the last 22 years, with the hottest four within the past four years, according to the World Meteorological Organization (WMO).

Figure 1 illustrates this warming trend. The graph shows the deviation in global surface temperatures relative to the average temperature in 1951-1980 (in °C). The comparison is over the period 1880 to 2020.

Figure 1 – Deviation in global temperature (°C) vs the 1951-1980 average

Rising temperatures can be felt in many regions of the world. In 2018 and 2019, Europe was hit by heatwaves that impacted harvests as well as water levels in rivers that communities and businesses rely on. June 2019 was the hottest June ever recorded, while a new record was set in France which reported its highest temperature ever at 45.9°C.

This rise in temperatures has led to other gradual changes such as melting ice sheets and higher sea levels. Arctic sea ice is declining at a rate of 12.8% per decade, while sea levels have been rising by an average of 3.3mm every year since 19933.

These changes are not just one-off events. They have a fundamental, long-term impact on economies and businesses. Many will need to adapt to longer periods of droughts and sea level changes in coastal regions.

Extreme weather events are causing considerable damage

In addition to gradual changes, we are experiencing more frequent and extreme weather events such as hurricanes, wildfires and floods. These cause loss of life as well as major disruption and economic losses.

Wildfires devastated California in 2018, shortly after the month of July which marked the US state’s hottest month on record. In June 2019, California had nearly 240 wildfires within one week, another record month. While wildfires occur naturally, record temperatures create the ideal dry conditions for them to occur more intensely and with greater frequency.

A few weeks later, Mumbai in India experienced its most severe flooding in 14 years due to extreme heavy rain. More than 30 lives were lost in the floods.

Figure 2 shows the increase in extreme weather events related to flooding (hydrological) and extreme temperatures that cause droughts and more frequent and intense wildfires (climatological). The rising trend is alarming.

Figure 2 – Increase in number of extreme weather events4

2. What is causing these changes?

The most significant contributing factor to this rise in temperatures is an increase of greenhouse gases (GHG) in the atmosphere. These gases are illustrated in Figure 3 and their source by economic sector is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 3 – Global greenhouse gas emissions by gas type

Figure 4 - Global greenhouse gas emissions by economic sector

Greenhouse gases vary in their global warming potential. For example, one tonne of methane has 28 times the warming impact of one tonne of carbon dioxide over a 100-year period, and the factor for nitrous oxide is 265. The warming potential of all GHG is translated into carbon-dioxide equivalent (CO2e) values to have a common basis of measurement.

Carbon dioxide emissions are mainly caused by the burning of fossil fuels such as coal, oil and gas. Coal produces the highest level of CO2 per unit of energy generated5, nearly twice the level of natural gas which is the least carbon-intensive fossil fuel. Gas is therefore often considered a useful ‘transition’ fuel.

But it is not only the burning of fossil fuels we need to worry about. Around a quarter of global emissions comes from agriculture and food production according to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). The main source of this is methane, which is a by-product of the digestive process of cattle. To quote a recent Barclays report6: ‘Burping cows cause more GHG emissions than all cars globally’. This source of emissions receives far less attention than fossil fuel users and producers. Barclays estimate that over the next 30 years, based on current trends, methane emissions from cattle will increase by 15%.

Global emissions continue to rise.

Analysing ice cores tells us that CO2 levels remained below 300 ppm (particles per million) over the last 400,000 years. During the industrial revolution in the 19th century, CO2 emissions began to rise. Today, atmospheric CO2 concentrations are at the unprecedented levels of 412 ppm7.

3. Who are the biggest contributors to GHG emissions?

It is important to understand which countries have the highest levels of GHG emissions and where action needs to be focused to reduce the effects of global warming.

Cumulative emissions – Who has contributed most over time?

For most of the 19th century, global cumulative emissions were dominated by European countries. The cumulative contribution of the United States began to rise in the second half of the 19th century and peaked at 40% in 1950. It has declined to approximately 26% since then, but the US remains the largest cumulative contributor in the world. By 2015, China accounted for 12% of total cumulative emissions, and India for 3%8.

Historically, there has been a strong link between fossil fuel usage, CO2 emissions and economic growth. This does not, however, need to be the case for the future. The energy transition is changing the way economic growth can be fuelled. With more affordable renewable energy, developing markets have an opportunity to grow without emitting the way developed countries did in the past.

Current emissions – Who continues to aggravate the problem today?

Over 60% of CO2 emissions in 2014 were generated by a handful of countries. China is by far the largest emitter, accounting for 26%, followed by the US (14%), EU-28 (9%), India (6.7%) and Russia (4.8%)9. These country emissions are production-based and do not take account of exports and imports. That means some of the CO2 emissions attributed to Asian and Eastern European countries are linked to the production of goods consumed in Western Europe and the US.

According to the Global Carbon Project, if we considered the emissions of consumption (including imports and exports), the 2014 CO2 emissions of many European economies would increase by more than 30% and US emissions would increase by 7%. On the other hand, China’s emissions would decrease by 13%, and India’s by 9%10.

Figure 5 – Annual share of global CO2 emissions, 2014 (excluding land use and forestry)

Population size matters for fair comparison. In per capita terms, China’s emissions of 7.5 tonnes of CO2/person (2014) are comparable to the global average and most European countries. This is much lower than in the US, the Middle East and Australia where we observe the highest per capita emissions of around 20-25 tonnes of CO2/person.

But ultimately, it is the absolute emission levels that need to be tackled by reducing the proportion of fossil fuels in the energy mix of large countries such as China and India.

4. What trajectory are we on now?

More than 180 nations committed to limiting GHG emissions at the 21st UN Conference of the Parties (COP21) in Paris in 2015. The milestone Paris agreement aims to limit warming to ‘well below’ 2°C from pre-industrial levels.

Member countries established Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) to achieve this goal, which resulted in more carbon emission reduction targets and climate change-related policies. There is progress, in some regions more so than in others, but the level of ambition and urgency to reach the goals of the Paris agreement remain underwhelming.

In 2018, the IPCC published a special report which compared the implications of warming by 1.5°C with the effects of a 2°C rise, and warned of severe consequences for people, economies and ecosystems if warming goes beyond 1.5°C.

The effects will be very unequal – hitting hardest the poorest and most vulnerable people in the least developed countries, dryland regions and small islands. This will result in migrants fleeing their homes to escape climate-change induced food poverty in sub-Saharan Africa, South America and South Asia.

Limiting warming to 1.5°C is still scientifically feasible but requires radical global action and urgent international cooperation. We are at some 1.1°C above pre-industrial levels today.

Global emissions will need to decline by 45% before 2030, and reach net zero by 2050. This will be expensive, as the marginal abatement costs for reaching 1.5°C are some three to four times higher than for the 2°C scenario. With current policies, we are on track for over 3°C warming by 2100, as shown in Figure 6 below.

In simple terms, there are two options. Governments around the world will either step up mitigation action with strong policies to achieve the goals of the Paris agreement, or they won’t. In the case of the latter, emissions will continue to rise, the physical impact will be more severe and increased investment in adaptation will be required to help minimise the effects.

Either way, money will have to be invested. We believe the first option is ultimately inevitable. Pressure on governments will increase as businesses and society demand action amid more severe and frequent physical damage.

The question is, how bad will the damage have to be before serious action is taken?

Figure 6 – Global warming pathways

Source: Climate Action Tracker (as of 2018)

Source: Climate Action Tracker (as of 2018)

‘Climate-related risks to health, livelihoods, food security, water supply, human security and economic growth are projected to increase with global warming of 1.5°C and increase further with 2°C’Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5°C, IPCC, 2018

’Natural disasters in 2017 caused overall losses of US$340bn. This was the second-highest annual loss ever and almost double the previous year’s level – a figure roughly equivalent to the annual GDP of Denmark, Egypt or Israel. Insurers had to pay out a record US$138bn in losses.’ MunichRe

Implications for Investors

Chapter 2

A warming planet and the transition to a low-carbon economy are changing the risk profile of assets, companies and economies. Every investment has some exposure to climate change risks but the materiality of the risks differs and can only be understood once identified and analysed.

Assessing the risks and opportunities of climate change should be a core part of the investment process. Fund managers and asset owners need to consider:

‘The explicit carbon-price level consistent with achieving the Paris temperature target is at least US$40 – 80/t CO2 by 2020 and US$50 – 100/t CO2 by 2030.’ - High-Level Commission on Carbon Pricing14

1. Transition risks and opportunities.

Governments could take strong climate change mitigation actions to reduce emissions and transition to a low-carbon economy. This is reflected in targets, policies and regulation and can have a considerable impact on high emitting companies.

2. Physical risks and opportunities.

Insufficient mitigation action leads to more severe and frequent physical damage. This results in financial implications, for example damage to crops and infrastructure, and the need for physical adaptation such as flood defences.

11An interactive map of all climate related legislation is provided by the Grantham Institute of Climate Change and the Environment: http://www.lse.ac.uk/GranthamInstitute/countries/

11An interactive map of all climate related legislation is provided by the Grantham Institute of Climate Change and the Environment: http://www.lse.ac.uk/GranthamInstitute/countries/

There is an important difference between the money invested in both scenarios. In the more ambitious energy-transition scenario, the money spent in mitigation today is an investment into the future that can generate a return. In the business as usual scenario, the higher financial damage due to physical climate impacts is purely a cost. The argument in favour of investment today is compelling.

1. The energy transition – risks & opportunities

The energy transition is underway in many parts of the world. We are seeing policy changes, falling costs of renewable energy and a change in public perception.

Many countries are stepping up climate action to deliver on their contributions to the Paris agreement. In China, for example, 20% of energy is due to come from non-fossil fuel sources by 2030. In the European Union (EU), there are clear targets to generate 32% of energy from renewables by that date and achieve net zero emissions by 2050. In June 2019, the UK was the first country to legislate a net zero emissions target by 2050. To make this happen, policies and regulations such as carbon pricing are being put in place. There are approximately 1,400 climate change relevant laws worldwide11. The challenge is to make them more ambitious and effective in reducing emissions.

1.1 Energy transition-related risks

This section provides examples of three different types of transition risks – carbon pricing, stranded assets and reputational risk.

1. Carbon pricing

One of the most effective ways to transition away from carbon-intensive energy sources would be to price carbon effectively, ideally at a global level to avoid effects on competitiveness. A sufficiently high carbon price would encourage fuel switching to low-carbon energy sources and impose considerable costs on businesses that fail to reduce emissions.

This view is supported by our paper, Going Green, which showcases our proprietary model of climate policies and their impact on emissions12. The announcement or implementation of a carbon pricing scheme is positively correlated with a reduction in GHG emissions.

In 2019, around 20% of global emissions are covered by 46 national and 28 subnational carbon pricing schemes13. These include carbon taxes and emission trading schemes. Carbon prices vary across countries, but have one thing in common: they are generally too low. Some 51% of emissions covered are priced at less than US$10/tCO2. In the EU, carbon prices have risen considerably over the past couple of years – from around €4/tCO2 in 2017 to €30/tCO2 in mid-2019. But this is still not sufficient for reaching the goals of the Paris agreement.

Companies should use an internal carbon price in their business planning that is consistent with the goals of the Paris agreement to understand the potential financial effects of rising carbon prices.

2. Stranded asset risk

Key to the energy transition is moving away from carbon-intensive fossil fuels and towards renewable energy sources, while ensuring secure energy supplies for a growing population. Phasing out coal-fuelled power generation would be a good start. To achieve the goals of the Paris agreement, the IPCC reckons that EU and Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries would need to be coal-free by 2030, with the rest of the world coal-free by 2050. A coal divestment movement is emerging that is reflected in initiatives such as the Powering Past Coal Alliance.

Countries including Ireland and Norway are divesting from fossil fuels in their national investment funds. Financial institutions are starting to limit lending for fossil fuel projects, therefore impacting the cost of capital for equity and debt financing.

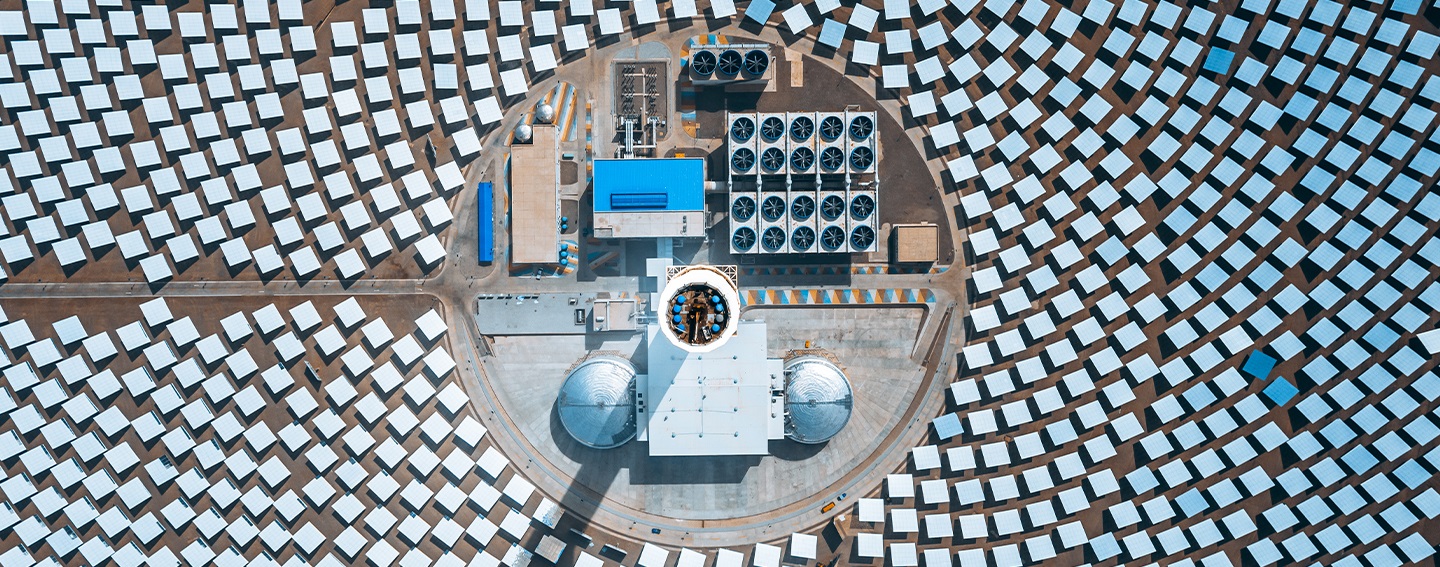

It also makes financial sense to move away from coal. The cost of renewable power generation has fallen so much in recent years that solar photovoltaic (solar panels) and wind electricity generation are already cheaper than new coal and gas plants in around two-thirds of the world. This will be the case almost everywhere by 2030, according to Bloomberg15.

Figure 7 compares the levelised cost of electricity (LCOE) across different energy sources16. It shows that solar photovoltaic (non-tracking, indicating that it is fixed and does not follow the sun) and onshore wind are already below the cost of coal and gas in several countries across Europe, China, India and the US (the largest GHG emitters).

Figure 7 – Levelised cost of electricity (LCOE in $/MWh) of different energy sources across selected countries, H1 2019

These divestment trends and falling renewables costs increase the risk of fossil fuel assets being ‘stranded’. Stranded assets can unexpectedly lose their value due to changes in demand during the transition to a low-carbon economy. They can include fossil fuel reserves, coal plants or gas infrastructure. The issue is intensified for fossil fuel companies with large amounts of reserves underground that may not be used, but are included in earnings assumptions or asset valuations.

Coal may be the first to be affected, but other energy sources, such as oil and gas, are expected to follow. Research undertaken by Carbon Tracker, an environmental think tank, suggests fossil fuel demand will peak in the 2020s, some 10 to 20 years sooner than estimates by the International Energy Agency (IEA) and scenarios developed by oil and gas companies, such as Shell and BP17.

The exact timing of this tipping point is uncertain and will depend on factors such as the pace of deployment and falling cost of renewable energy, growth in energy demand and ambition of climate mitigation action.

Businesses with fossil fuel-related assets on their balance sheet need to consider that the value of their assets might drop significantly, potentially much sooner than they may expect.

3. Reputational risk

Public concern around climate change is growing. Protests by the climate activist group ‘Extinction Rebellion’ are a very visible example of this.

But changing opinions are also reflected in the shifting demands of clients and shareholders. Many have higher expectations of corporates and governments to demonstrate action on climate change. The demand for low-carbon products is increasing. Where businesses fail to demonstrate they have met their responsibilities, they face financial, reputational and litigation risks.

1.2 Energy transition-related opportunities

The International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates that achieving a Paris-compliant energy transition requires around US$3 trillion in investment every year, mainly in renewables and energy efficiency.

Figure 8 illustrates the growth required in energy transition solutions for two different IEA scenarios: the New Policies Scenario which reflects current NDC commitments; and the Sustainable Development Scenario which aims to be aligned with the Paris goals.

‘The explicit carbon-price level consistent with achieving the Paris temperature target is at least US$40 – 80/t CO2 by 2020 and US$50 – 100/t CO2 by 2030.’ - High-Level Commission on Carbon Pricing14

Figure 8 – Energy transition growth scenarios

‘The explicit carbon-price level consistent with achieving the Paris temperature target is at least US$40 – 80/t CO2 by 2020 and US$50 – 100/t CO2 by 2030.’High-Level Commission on Carbon Pricing14

Wind and solar

PV generation

Electric

Car Fleet

Energy

productivity

CCUS

deployment

Share of

non-fossil fuels

As the share of non-fossil fuels needs to double by 2040 to achieve the Paris goals, the opportunities for investment into low-carbon energy sources and technologies are considerable.

1. Renewable energy generation & storage

The growth in renewable energy required to meet the Paris goals is considerable. Investment in energy storage and transmission is also needed to address the intermittency issues of renewable energy and to enable a higher percentage of renewables on a power grid. The 2019 Bloomberg New Energy Outlook provides an indication of what’s needed.

‘A 12 TW (terawatt) expansion of generating capacity requires about $13.3 trillion of new investment between now and 2050 – some 77% of which goes to renewables. Another $843 billion of investment goes to batteries and an estimated $11.4 trillion to transmission and distribution.’Bloomberg New Energy Finance, New Energy Outlook 2019.

2. Energy efficiency

Under the New Policies Scenario, energy demand is expected to grow by 25% by 2040. Using this energy efficiently – in buildings, industry and transportation – is going to be vital. Regulations, such as the Minimum Energy Efficiency Standards (MEES) for buildings in the UK and the fuel efficiency standard regulation in Europe, are already in place in many regions to encourage this. While these impose additional costs for some sectors and businesses, they also provide opportunities for others to tap into new energy-efficient technologies and products.

3. Electrification of transport

The global electric car fleet exceeded 5.1 million in 2018, 2 million higher than in 2017, according to IEA data. China has the largest number of electric vehicles globally, followed by Europe and the United States. By 2030, the global electric vehicle (EV) fleet could exceed 130 million vehicles in the New Policies Scenario. This provides investment opportunities along the whole EV value chain – from the provision of raw materials and the production of components such as batteries and fuel cells, to the final assembly of electric vehicles.

4. Carbon removal

Finally, it’s not just about reducing, but also removing CO2. Negative emission technologies such as Carbon Capture Usage and Storage (CCUS) are expected to play an important role in Paris-aligned scenarios. But the rollout of CCUS technologies is far behind schedule as can be seen in Figure 8. Carbon prices are too low to make CCUS a commercially viable investment opportunity. This may change in future depending on the stance that governments take on incentivising carbon removal.

1.3 Who’s going to be most affected by the low-carbon transition?

Those with high levels of CO2e emissions (considering the whole supply chain) generally face the highest levels of energy transition-related risks and opportunities.

They will need to invest in innovative, cleaner and more efficient technologies. There is a considerable cost associated with transitioning to lower-emission technologies for certain sectors and a risk of failed technology investments. New technologies must also be accompanied by a corresponding set of new skills in the workforce, which can be difficult to attract and retain.

Companies in the following sectors are most exposed:

1. Utilities (Power & Heat)

Utility companies generating power from fossil fuels face high transition risks, such as increasing costs from carbon prices and reputational pressures.

2. Industry

Production of cement, steel and iron are particularly carbon intensive and difficult to decarbonise. These industries are at risk of losing competitiveness where carbon prices are in place because of ‘carbon leakage’. This means materials can be imported from regions without carbon prices at lower cost.

3. Transportation

While electrification of passenger vehicles is making good progress, decarbonising long-range transportation such as trains, planes and ships is a challenge due to limitations in battery technology. Some regions, such as the EU, also have stringent fuel efficiency standards that put cost pressures on auto manufacturers.

4. Energy

While the direct emissions of fossil fuel energy companies are lower compared to the three industries mentioned above, their downstream emissions related to the consumption of fossil fuels products are significant. Fossil fuel producers also face the risk of stranded fossil fuel-related assets.

Channelling capital towards high-emitting companies that have ambitions to transform their businesses and align themselves with the Paris goals is critical for enabling the energy transition.

Company Example

The Danish power company Orsted is a good example of transformation driven by the energy transition. It is one of the largest global renewable energy generators today, but was previously known as DONG Energy, a traditional oil and gas company. The company sold its oil and gas business in 2017, committed to phasing out coal and re-branded to reflect the change in its business model.

2. Physical impacts of a changing climate - risks & opportunities

In Chapter 1 we discussed the gradual (chronic) and sudden (acute) effects that can be observed in a warming climate. These include droughts, sea level rises and an increase in extreme weather events.

Businesses affected by acute physical effects are likely to face short-term disruption and one-off costs. But gradual climate changes require long-term adaptation to a new ‘normal’.

2.1 Risks related to physical impacts

The negative implications of physical climate risks include:

- Damage to infrastructure

- Poor harvests

- Rising cost of assets and commodities

- Migration of climate-change refugees

- Operational risks in the supply chain

These have real financial implications for companies and economies. In addition, adaptation costs (e.g. infrastructure required to protect from physical damage) and the risk of insurance costs rising must be considered amid an increase in physical risks.

A recent Morgan Stanley report18 on the physical risks posed by climate change shows that, of the 710 most recent climate events, some 44% took place in Asia, inflicting economic damage equal to 0.66% of GDP. Only 23% of these events affected North America, but these made up some 83% of the total economic damage, or 0.24% of GDP. These extreme weather events cause temporary disruption at significant cost to economies and businesses.

In our view, three physical risks are particularly relevant for businesses:

Producing food the way we do today will not be feasible within a few decades.

Droughts and floods reduce the productivity of harvests and increase commodity prices. Wheat, for example, has been identified as particularly vulnerable. During the heatwaves in Europe in 2018, harvest yields were low and wheat futures prices reached a three-year high in August 2018. These factors cause seasonal short-term disruption to supply.

There is, however, a more important long-term consideration for agriculture. Higher temperatures increase the amount of water vapour in the atmosphere which increases the chance of heavy downpours. These downpours cause soil erosion and will have a permanent, long-term impact on the world’s ability to produce food the way we do today.

‘In regular rain, even heavy rain, farmers lose very little soil. It is the one or two great downpours every few years that cause the trouble. We’re losing perhaps 1% of our collective global soil a year…It is calculated that there are only 30 to 70 good harvest years left, depending on your location. In 80 years, current agriculture will be simply infeasible for lack of good soil.’The Race of Our Lives, Jeremy Grantham, GMO, 2018

2.2 Opportunities related to increasing resilience via adaptation

There is a growing need for investment in adaptation to make businesses, cities and countries more resilient. Adaptation commitments are also an important part of the NDCs as part of the Paris agreement.

The United Nations Adaptation Finance Gap report, published in May 2016, highlights the need for some US$140 billion-US$300 billion per annum by 2030 to finance adaptation needs and increase global resilience to climate change. In 2014, international public finance assigned for adaptation was around US$22.5 billion. The adaptation finance gap is considerable and investors – both fund managers and asset owners – can play a substantial role in closing this gap.

‘To meet finance needs and avoid an adaptation gap, the total finance for adaptation in 2030 would have to be approximately 6 to 13 times greater than international public finance today.’United Nations Adaptation Finance Gap report, May 2016

A number of areas deserve particular attention for adaptation opportunities:

1. Infrastructure

Coastal cities, for example, require engineered protection from sea level rises. A global analysis of 136 coastal cities reported indicative annual adaptation costs of US$350 million per city, or approximately US$50 billion annually in total19.

2. Water and soil management

Investment in water efficiency, restoring the water supply-demand balance and addressing the issue of deteriorating soil quality. This is particularly important in agriculture, but also other water-dependent sectors in water-stressed regions.

3. Technology

Growing demand for certain technologies (existing and new), e.g. rising heat in buildings leading to the growing need for cooling equipment. Innovative technologies to reduce water intensity and make water usage more efficient.

2.3 Who is going to be most affected by the physical risks?

Physical risks exist for all sectors and are affected by location, as well as the nature of the business (e.g. supply chain/operations dependent on water or agricultural outputs).

Increased levels of warming will make a considerable difference in certain regions and industries, particularly:

1. Businesses heavily reliant on water

Water scarcity is going to be a major issue across a number of regions. Certain industries will be particularly impacted including food and drink, agriculture, energy, data centres, semiconductors, cement and water utilities.

Company Example

Anheuser-Busch InBev produces beer and distributes its products to customers around the world. Water risk is material for their business given the water intensity of the brewing process, their operations, and reliance on raw materials which are often cultivated in water-stressed regions. They monitor water stress results quarterly using the World Resource Institute Aqueduct tool20. Currently, 25% of their volumes are produced in water-stressed areas. This is expected to increase substantially due to climate change. Managing their water risk and reducing the water intensity of their operations is therefore essential.

2. Real estate

Damage to real estate will increase with a rise in extreme weather events such as floods, storms and fires. This can affect any business with real estate in vulnerable locations such as coastal regions, as well as investors in real estate assets. The location of assets and revenue generation should be disclosed by businesses as standard practice to provide more transparency on the potential impact.

3. Insurance

Damage to assets will result in higher payouts by insurance companies. The increase in frequency and severity of physical risks should be priced in. Some are doing so already. For example, reinsurer MunichRe uses natural catastrophe data from their NatCat Service (as featured in Chapter 1).

4. Businesses reliant on agricultural commodities

Droughts and floods reduce the productivity of harvests and increase commodity prices. Businesses that are reliant on agricultural commodities for their operations will be affected by supply shortages, higher prices and the longer-term trends affecting food production.

These businesses must assess the effects of a warming planet on their supply chain, operations and customers, and reflect this in their risk management and business planning.

Summary of risks by sector

A high level summary of key climate change risks by sector is provided below.

Source: Aberdeen Standard Investments (2019)

Source: Aberdeen Standard Investments (2019)

In summary, climate change poses different challenges across different sectors. For each sector and region, we need to understand the potential physical impact of climate change and the implications of the low-carbon energy transition. This process will change the risk profile for many of the assets we invest in and is therefore an important part of our investment decision-making process.

Managing the Issue

Chapter 3

Climate change and the energy transition are transforming the risk profile of companies and economies around the world. Fund managers need to take this seriously. They have a responsibility to clients to consider how these changes will impact the value of their investments.

Climate change has profound implications for the planet. We all have a role to play in tackling the biggest challenge of our lifetimes. Asset managers have a particularly important role to play in financing the transition to a low-carbon economy.

‘We all have a role to play in tackling the biggest challenge of our lifetimes. Asset managers have a particularly important role to play in financing the transition to a low-carbon economy.’

We have aligned our own approach with that advocated by the investor agenda of the Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI) – a United Nations-supported initiative to promote responsible investment as a way of enhancing returns and better managing risk.

PRI provides an intellectual framework to steer the massive transition of financial capital towards low-carbon opportunities. It also encourages fund managers to demonstrate climate action across four areas: investments; corporate engagement; investor disclosure; and policy advocacy.

Figure 9 shows how these principles can be applied in practice.

Figure 9 – ASI’s climate change approach

Source: Aberdeen Standard Investments, May 2019

Source: Aberdeen Standard Investments, May 2019

It’s worth elaborating on a few of the points raised above:

1.Research

High-quality research drives investment decisions and positive outcomes. This includes climate-change research. Fund managers should consider having a dedicated climate-change analyst within their investment research team. This specialist researcher would be able to give insights on key regulatory and industry trends across regions and study specific climate-related risks and opportunities.

2. Investment integration

Fund managers should incorporate climate-change research as an integral part of their investment process, across asset classes. It is important to identify the climate-change risks and opportunities that a country, sector, company, or real asset is facing, and assess their financial materiality.

While the risks of climate change are clearly important, what’s often overlooked are the opportunities. Whether or not we can limit temperature rises will depend on whether the world is able to quickly deploy large amounts of private capital to construct renewable energy infrastructure, low-carbon transport and improve energy efficiency.

3. Corporate Engagement

Fund managers who regularly engage with investee companies are better able to understand their exposure and management of climate-change risks and opportunities. In actively managed investments, ownership provides them with a strong ability to challenge companies where appropriate, and influence corporate behaviour in relation to climate-risk management.

Through active engagement, asset managers can steer investee companies towards ambitious targets and sustainable low-carbon solutions. If there is limited progress in response to engagement efforts, they should consider the power of voting, shareholder resolutions and, as a last resort, selling their holdings.

Exercising influence through engagement can work particularly well in collaboration with other asset managers and asset owners. For example, we do this through involvement in Climate Action 100+, a five-year initiative to collectively engage and influence high-emitting companies.

4. Collaboration and influence

Providing support for, and actively engaging with, a range of climate-change associations and initiatives helps the shift towards a low-carbon economy. Fund managers can collaborate with industry associations, such as the Institutional Investors Group on Climate Change (IIGCC), on a number of initiatives to encourage action and transparency of data for the companies within their portfolios. We are active members of the IIGCC and participate in several working groups.

Policy advocacy is important. The low-carbon transition is dependent upon the development of government policies to remove barriers and provide incentives. For example, we have signed the 2018 Global Investor Statement to Governments on Climate Action to demonstrate our support for governments to strengthen climate-related policies.

5. Disclosure

Fund managers should disclose climate-related data in line with the framework advocated by the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD). The main objective of the TCFD’s recommendations is to encourage organisations to evaluate and disclose the material climate-related risks and opportunities that are most relevant to their business activities. This is expected to increase climate-related data transparency and make the financial system more resilient to climate-related risks.

Working towards reporting in line with TCFD requirements involves reporting on two levels: Operational – climate-change-related activities, processes and emissions at group level are reflected in the recommended disclosures made for all sectors; and Investments – focused on the impact of climate-change risks and opportunities on investments, as highlighted in the additional disclosure requirements for asset managers.

Figure 10 – TCFD disclosure recommendations

We are active supporters of TCFD and are in the process of writing our first TCFD report.

More data, better data

More transparency is clearly needed to understand how climate change will affect investment holdings. That would be more transparency from the companies fund managers invest in. It would also be more transparency from asset managers about the exact nature of climate-change exposure within their portfolios.

We expect climate-related reporting requirements for asset managers to strengthen in line with the proposals of the European Commission’s Action Plan for Financing Sustainable Growth, and the Financial Conduct Authority’s discussion paper on climate-change and green finance. This will help increase transparency, consistency and quality of data across the industry.

How to assess climate risk in a portfolio

Reliable and robust climate-related data is critical for effective investment decision-making. Asset managers who are serious about tackling climate change should consider backward- and forward-looking measures that indicate climate risk exposure and the strategic direction of a company.

Carbon footprinting

Providing carbon-footprint reports for investment strategies across asset classes is a step in the right direction, and in line with the recommendations of the TCFD.

A carbon footprint measures the total greenhouse gas emissions caused directly and indirectly by a person, organisation, event or product. Greenhouse gases, such as carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane (CH4), contribute to global warming.

Emissions are measured in units of CO2e (carbon dioxide-equivalent), which track the impact of the different greenhouse gases in terms of the level of CO2 that would be needed to create the equivalent amount of warming.

Tracking carbon footprints helps fund managers understand a company or portfolio’s exposure to climate risks. It can help identify relatively carbon-intensive companies and drive corporate engagement. The process can also help decision-makers reduce the carbon footprint of a portfolio.

With access to accurate CO2e data, here are some of the things they can monitor in more detail:

- Total emissions in tonnes of CO2e (apportioned) – this reflects the amount of greenhouse gas emissions ‘financed’ by the portfolio. This is what countries and companies are under pressure to reduce.

- Relative emissions (relative to revenue or assets under management) in tCO2e/US$ – this reflects the carbon intensity of the company/portfolio. This data can be compared against a benchmark, other portfolios and peers.

- Attribution analysis – this demonstrates which sectors and/or companies contribute the most to a portfolio’s carbon footprint.

- Trend analysis – this reflects how emissions change over time and provides a baseline for comparison. Tracking change is important, as high emitters with a positive trend can be supportive of the energy transition.

That said, tracking carbon footprints has its shortcomings:

- It is a backward-looking measure and does not reflect strategy, targets and climate solutions that may be provided by the company.

- Data comparability across peers can be a concern due to inconsistency of reporting and information gaps.

- Lack of disclosure can be a challenge – smaller and private companies may not disclose emissions data. Asset managers should set a coverage threshold at portfolio level to decide whether data disclosure is good enough for meaningful portfolio carbon footprint analysis.

The origin of gas emissions is an important consideration. Scope 1 (direct emissions) and Scope 2 (indirect emissions from consumption of purchased energy) are generally reported on by companies. But Scope 3 emissions (taking account of upstream and downstream emissions along the value chain) are more difficult to obtain.

However, Scope 3 emissions are critical for understanding the true impact a company has on emission levels. In fact, in many cases, Scope 3 emissions make up the majority of a company’s total emissions. Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions are defined by the Greenhouse Gas Protocol, the global standard for measuring emissions.

One recommended approach (and the one that we’ve adopted) is to consider Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions at the company and sector levels, but to limit emissions considered for portfolio carbon footprinting to Scope 1 and 2. This helps avoid double counting and data inconsistencies.

Figure 11 – Portfolio carbon-footprinting example: model portfolio

Forward-looking assessments

In addition to emissions data, fund managers should consider other more forward-looking climate-related indicators for the companies they invest in. This includes the quality of climate-risk management, climate-change strategies and targets, scenario analysis outcomes, and emission forecasts.

The Transition Pathway Initiative (TPI) can be a good start. The TPI assesses companies based on:

- GHG management quality – the quality of companies’ management of their greenhouse gas emissions, and of the risks and opportunities related to the transition to a low-carbon economy.

- Carbon performance – how companies’ current and future carbon performance might compare to the international targets and national pledges made as part of the Paris agreement.

Scenario analysis is important and probably the most challenging component of the TCFD recommendations. It helps investors – asset owners and fund managers – to understand the impact of different climate-related scenarios on investments and products.

We currently undertake scenario analysis for selected companies and portfolios to assess positioning against a 2°C warming scenario, using publicly available tools. Our aim is to continue to expand the scope of this analysis and to obtain more quantitative outcomes.

‘We all have a role to play in tackling the biggest challenge of our lifetimes. Asset managers have a particularly important role to play in financing the transition to a low-carbon economy.’

Conclusion

Our climate is changing. This is one of the most significant challenges of the 21st century and it has big implications for investing. A growing population means rising demand for energy and food. This comes with an increase in greenhouse gas emissions and temperatures if we don’t urgently transition to low-carbon energy solutions.

Companies and economies will face significant investment and other financial burdens during the global transition to low-carbon energy sources. As countries step up climate action to reach the goals of the Paris agreement, transition risks are becoming more material. These include policy risks such as rising carbon prices, stranded asset risk as some assets will become obsolete, and reputational risk – businesses that fail to demonstrate action will incur public and shareholder censure.

That said, transition to the ‘new normal’ also brings opportunities. Considerable sums of private capital will be needed to cover the shortfall in investment required for the shift towards a low-carbon economy. There will be opportunities in renewable energy, energy efficiency and storage, electric vehicles, new low-carbon fuels such as hydrogen, and potentially, carbon removal solutions.

‘Ultimately, asset managers have a responsibility to their clients to consider the impact of climate change on investment value. This involves gaining an intimate understanding of how each company is exposed to material issues related to climate change, and what these companies plan to do to tackle these challenges.’

On the other hand, if action to limit global warming is insufficient, there will be costs from increasing physical damage linked to climate change. Businesses will experience more frequent and severe physical impacts across the whole supply chain. This will include damage to infrastructure and disrupted operations, water stress, poor harvests and more expensive assets and commodities.

Considerable investment will then be needed to cope with the physical impact of climate change. Adaptation will require new infrastructure, better water and soil management, as well as new technology such as cooling equipment to be better prepared for long-term disruption.

Fund managers need to treat these risks seriously. They need to incorporate specialist ESG research into their investment process, enhance corporate engagement, boost collaboration with others who can help effect change and support better disclosure. They also need to clearly articulate and demonstrate how they have integrated climate change into their decision-making process and disclose relevant data to meet the changing demands of clients and regulators.

Ultimately, asset managers have a responsibility to their clients to consider the impact of climate change on investment value. This involves gaining an intimate understanding of how each company is exposed to material issues related to climate change, and what these companies plan to do to tackle these challenges.

1 Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5°C, IPCC, October 2018

2 21st UN Conference of the Parties (COP21) held in Paris in December 2015

3 Source: https://climate.nasa.gov/vital-signs/arctic-sea-ice/, NASA, accessed July 14 2019

4Accounted events have caused at least one fatality and/or produced normalised losses >=US$100k, US$300k, US$1m or US$3m (depending on the assigned World Bank income group of the affected country)

5Coal releases in the range of 214-228 CO2/Btu (British thermal unit) depending on the type of coal, oil in the range of 157-161 CO2/Btu and gas in the range of 117-139 CO2/Btu.

6Barclays Equity Research, Global Agriculture, Winds of Change: The next environmental debate, Feb 2019

7National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), measured in June 2019

8Our World In Data, https://ourworldindata.org/ . Accessed July 14 2019.

9CAIT Climate Data Explorer, 2015. Washington, DC: World Resources Institute. Available online at: http://cait.wri.org. Accessed August 13 2019.

10https://www.globalcarbonproject.org/carbonbudget/

11An interactive map of all climate related legislation is provided by the Grantham Institute of Climate Change and the Environment: http://www.lse.ac.uk/GranthamInstitute/countries/

12Aberdeen Standard Investments, Going Green, September 2019

13The World Bank, State and Trends of Carbon Pricing 2019, June 2019. All carbon pricing schemes can be viewed in the World Bank carbon pricing dashboard: https://carbonpricingdashboard.worldbank.org/

14Carbon Pricing Leadership Coalition, Report of the High-Level Commission on Carbon Pricing, May 2017.

15Bloomberg New Energy Finance, New Energy Outlook 2019.

16The LCOE indicates the present value of the cost of electricity generation over the lifetime of the asset. The mid-point presented here has been calculated based on a range of low and high values sourced from Bloomberg New Energy Finance, New Energy Outlook 2019.

172020 Vision: Why You Should See The Fossil Fuel Peak Coming, Carbon Tracker, September 10 2018

18Morgan Stanley, Physical Risks and Opportunities Emerging, February 2019

19United Nations Adaptation Finance Gap report, May 2016

20World Resource Institute, https://www.wri.org/aqueduct

21Some other production methods are in the early stages of development such as coal gasification and the use of biomass for hydrogen production.

22Morgan Stanley, Global Hydrogen – A US$ 2.5 trillion industry, July 22, 2018